2020 marks the 100 year anniversary of John Dos Passos’s first published novel, One Man’s Initiation: 1917. In this blog post, Lisa Nanney – author of John Dos Passos & Cinema and editor of The Paintings and Drawing of John Dos Passos, both published by Clemson University Press – assesses the novel’s beginnings, rooted in the author’s experience of World War I.

“Horror is so piled on horror that there can be no more”

– John Dos Passos on World War I

As a generation of millennials navigating the dislocations caused by the current pandemic are discovering, the initiations we undergo as we come of age become part of us for the rest of our lives. In One Man’s Initiation: 1917, published a century ago this year, John Dos Passos re-created the defining experience of his own passage to adulthood—surviving the harrowing battlefields of World War I.

Being immersed in the war compelled the twenty-one-year-old Dos Passos to commit to words its lived experience. But conventional narrative methods seemed inadequate to him to convey to future readers the unwelcome revelations thrust upon him at Verdun and other scenes of carnage and decimation. In his search for aesthetics equal to such experiences, he began shaping the modernist innovations that would plunge readers into the immediacy and dynamism of early twentieth-century America in his novels of the later 1920s and 1930s, Manhattan Transfer and the U.S.A. trilogy, and in the filmic techniques he evolved for the page and the screen in the 1930s. One Man’s Initiation: 1917 is one hundred years old, but it and the story of its creation jolt us into an awareness of how the trials we endure in our youths—whether war or home-grown violence or hardship or diaspora or pandemic—inevitably construct the ways we articulate the world we find afterward.

When Dos Passos began trying to enlist in the U.S. armed forces in 1916, he was twenty years old, just graduated from Harvard, already politically radical. He had published anti-war essays deploring the military industrial complex and the capitalist interests that supported it. Even though he wrote that World War I was a “tidal wave [of] blood and fire . . . grinding the helpless nations,” he pressured his conservative father to allow him to join the military at the outset. As did many other Lost Generation writers, he felt impelled to be involved in the cataclysm that was reshaping Europe and consuming the lives of his contemporaries. Finally able to enlist early in 1917, he joined the Norton-Harjes volunteer ambulance corps, serving with the Red Cross. By summer he was at the Verdun front, surrounded by German shelling and poison gas, and, by early 1918, under fire in Italy. Letters Dos Passos wrote from there to friends in the U.S. and Spain made clear his contempt for the war: “a vast cancer fed by lies and self seeking malignity on the part of those who don’t do the fighting.” Yet, he declared, he was “happier…in the midst of it than in America, where the air was stinking with lies & hypocritical patriotic gibber.” Charges of disloyalty ensued when Red Cross authorities intercepted his mail; they recommended that he be dishonorably discharged.

The censorship and threat of punishment for speaking openly seemed merely to validate his views, but the charge threw his continued service into jeopardy and quashed his outgoing communications. Instead of writing letters, then, while waiting for the authorities to adjudicate his case, he crafted the novel that became One Man’s Initiation: 1917.

Though he had been writing at an apprentice novel while at Harvard, he now recognized that the conventional methods he had absorbed from his education were ineffectual to convey the world the war had made. Witnessing the violence threatening to destroy centuries of European culture, he wrote to a friend in 1917 that he wanted to create “a novel called the Dance of Death…but all my methods of doing things in the past merely disgust me now…damned inadequate. . . . Horror is so piled on horror that there can be no more.” The style he subsequently forged presaged the signature innovations of his next four novels. In this closeup narrative of the Great War from the perspective of one of its millions of soldiers, Romantic painterly visions of the bucolic French countryside are abruptly succeeded by shockingly Expressionistic frames of dismemberment and death in a cinematic method explored in my 2019 book John Dos Passos & Cinema. One Man’s Initiation immerses us along with the soldiers in the haze of explosions, the pervasive almond of poison gas, and the relentless din of artillery; through the ambulance drivers’ cloudy gas masks we see dimly the ruined cathedrals in the blasted landscape, the dying wagon-mules and human bodies left lying in the trenches where they were felled. Dos Passos’s satiric vision emerges in the specter of a carved wooden crucifix ripped from the altar of an ancient church and planted in the mud at a camion crossroad; the Christ’s crown of thorns has been replaced with barbed wire.

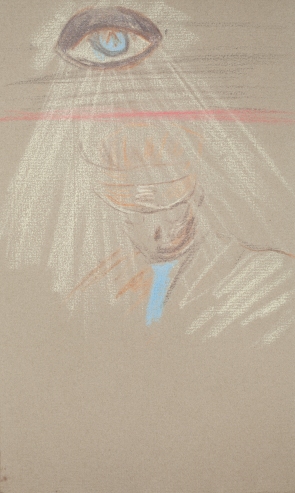

The powerfully visual quality of such scenes suggests how informed by the visual arts the young writer’s work already was in this novel; he had begun to “think in gargoyles,” he declared in a 1917 letter. Even this early in his career, his own practice of painting and drawing, which became a lifetime avocation, revealed the dialogue between the narrative and the visual that defined the dynamics of his later modernist work. A quick pastel crayon sketch from a notebook he kept during 1917-19, in combat zones and between postings, visualizes the sense of horror that permeates One Man’s Initiation: 1917. (See illustration from The Paintings and Drawings of John Dos Passos, ed. Pizer, Nanney, and Layman, Clemson University Press, 2016.) In this enigmatic image, beams of yellow emanating from an eye-shaped blue fixture illuminate a roughed-in head below. It wears a doughboy’s cap but only shadows delineate its skull-like empty features. Ambiguously but ominously, the sketch suggests the individual’s—or the artist’s—consciousness opening wide to the awareness of mortality the war made inescapable.

Sketch by John Dos Passos, 1917-19. Pastel, notebook paper, 9 1/4 x 5 3/4. By permission of Lucy Dos Passos Coggin

Dos Passos’s better-known modernist novels of the 1920s and 1930s, Manhattan Transfer and the volumes of U.S.A., likewise visualize and encompass other vast and nearly incomprehensible subjects—New York City, and the American nation itself. These ambitious works plunge readers into the anonymous trajectory of history in the midst of which individuals, like the one man of the early war novel, struggle to define their individuality against the monolithic forces of militaries, governments, economies, technologies, cities, politics, and the manipulations of language in public media that define contemporary modern life at least as much as in the century introduced by One Man’s Initiation: 1917 and initiated by the Great War.

For more information on John Dos Passos & Cinema visit the book’s listing on our website.